Millets should ideally be referred to as “past crops that have been ruggedized for the future.” They are nutritious, gluten-free, nutrient-dense, and drought-resistant, and can withstand the harsh effects of climate change. They develop and expand quicker than rice and wheat. Thus, government attempts to promote millets are unquestionably significant. Now is the time for India’s private sector to step up and contribute in areas such as food processing and hotels.

Introduction

Millets were a major crop consumed in India and numerous other nations about five decades ago. According to a 2014 National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) report, the plate share of millets has declined significantly in favour of wheat, rice, and processed foods. As a result of increased land use for wheat and rice production, the cultivation area for millets has decreased by 58% for small millets, 64% for sorghum, 49% for finger millet, and 23% for pearl millet since 1956. Millets are considered to be the sole crop that will handle critical challenges in the future such as food, fuel, malnutrition, health, and climate change.

With India’s growing malnutrition problem—both undernutrition (vitamin, mineral, and protein deficiencies) and overnutrition (obesity, metabolic syndrome, and lifestyle diseases)—there is a growing awareness of the need to move to healthier, more accessible, and inexpensive diets that include millets. In addition to being naturally gluten-free and nutrient-dense, millets are also a rich source of protein, essential fatty acids, dietary fibre, and vitamin B.

When it comes to the global scenario of millet production, India is the top producer of millets in the world and the fifth-largest exporter of millets globally. As the demand for millets rises quickly, their exports are expanding dramatically. More business opportunities are being created for entrepreneurs as millets’ demand rises. The millet market had a value of over USD 9 billion in 2018 and is expected to grow at a rate of over 4.5% from 2018 to 2025, with a value projection of over USD 12 billion.

Apart from creating business opportunities, millets also aid in the prevention of numerous non-communicable lifestyle diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease and are considered to be a potential choice or solution to lessen the negative effects of rising malnutrition and to improve the food and nutrition security of the nation. Due to their adaptability to a wide range of temperatures and moisture regimes, as well as their low input requirements, millets are resistant to climate change. They are resilient crops with small water and carbon footprints. Millets can withstand droughts and can even survive on 350–400 mm of rain, making them an ideal crop for production.

As proposed by India to the Food and Agriculture Organization, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution declaring 2023 as the International Year of Millet. The main goal of this initiative is to raise public awareness of the health benefits of millets and their suitability for cultivation under challenging conditions brought on by climate change. The International Year of Millet provides an excellent chance to:

1. Improved millet’s contribution to food security

2. Increase millet output globally.

3. Making sure that the processing, transport, storage, and consumption are efficient

4. Sustainable millet production and quality with stakeholder participation

Millet farming is still an area with a lot of room for ecosystem-level interventions. Promoting millets not only raises awareness of these wonder crops but also of women farmers and their farming knowledge. Raising awareness among farmers and the general public about the numerous benefits of millet can help revitalize millet production and consumption in India.

The great millet story

Today millets are known as super grains for the huge health, economic, and environmental benefits theyoffer. The Indian government, the United Nations, the fitness experts, startups, FMCG giants, and almost everyone who is health conscious is talking of millets. And to think it was once known as inferior coarse grains.

And of course, the United Nations has declared 2023 the International Year of Millets, and the Indian government has released a massive publicity campaign to promote millets. And to think it was this millet that was very much a part of soldiers’ daily food about half a century ago, but it lost favour to wheat and rice, in the Army as well as across India, after the Green Revolution led to bumper crops of rice and wheat and the government’s public distribution system doled out these staples as subsidized grains. Now the Indian Army wants its soldiers to eat millets. Twenty-five per cent of the authorized entitlement of cereals (rice and wheat atta) in troop rations will now be millet flour. The Army is not following a health fad.

Traditionally, India’s consumption basket was well-balanced, with evidence of consumption of nutrient-rich millets dating back to 3000 BC. However, after the Green Revolution, the trend reversed. While millet yield in India tripled from 414 kg/ha in 1961 to 1,352 kg/ha in 2021, the percentage of area under millets halved from more than 30 million ha to 13.6 million ha in the same time period.

A similar trend was observed at the global level, where the average yield increased from 592 kg/ha to 972 kg/ha while the total area under harvest saw a considerable decline from 43.4 million ha to 30.9 million ha in the same time period.

So how was millet rediscovered? A dispute had broken out in 2015 over poor villagers in the drought-hit Bundelkhand region of Uttar Pradesh who were managing to survive by eating rotis made of grass. Later, it was argued by some that it wasn’t grass but a kind of grain that had fallen out of use decades ago with the wider prevalence of wheat and rice. It was a local variety of millet that grew wild as well as could be sown. Since that millet variety was drought-resistant and could be stored for years, it was the staple for local people in times of repeated crop failures.

It is not surprising to know that millets were always considered inferior to wheat and rice and were known as ‘mota anaaj’ or coarse grain, as opposed to the fine grain of wheat and rice, which taste better and are easier to process and cook. However, millets remained in use because they were an essential part of ethnic cuisine. Most ethnic dishes across India are made of one type or another of millet. Even in rice-wheat states such as Punjab and Haryana, where other food crops were nearly wiped out, dishes such as Bajra khichdi remained popular.

In states such as Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Maharashtra that are drought-prone, millets remain part of the daily diet in several regions. According to an estimate, millets made up around 40 per cent of all cultivated grains before the Green Revolution. Now they are just around 20 per cent.

India’s PM Modi is diligently endorsing and promoting millets and has named them Shree Anna. Shree Anna is the new name the government has invented for millets, which roughly translates to blessed food. No wonder the Kashi Vishwanath temple in Modi’s own parliamentary constituency, Varanasi, has decided to offer devotees ‘prasad’ made from millets. The ‘laddu prasad’ at the temple will now be known as ‘Sri Anna prasad’. But that’s just one part of the millet promotion. Sri Anna is making waves all around, from Bill Gates cooking a Shree Anna khichdi with Union Minister Smriti Irani to Shree Anna dishes being served at the G20 meetings India is hosting.

The government is making all the right moves to highlight millet. Last year, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the “Millet Challenge” for startups, with a grant of Rs 1 crore to each of the three winners to encourage the design and development of innovative solutions for and across the millet value chain. The government’s focus on millets was also made clear in the Union Budget 2023, wherein it was announced that millets were “sri anna” and that the Millet Institution in Hyderabad would be turned into a centre of excellence. As per the Economic Survey 2023, there are over 500 startups working in millet value chains.

PM Modi has very aptly summarized why we need to shine the spotlight on millets—it is good for the consumer, the cultivator, and the planet. Millets are not mainstream yet. A combined effort of people, industry, government, and farmers will bring it back into mass consumption in India and globally.

The economy of millets

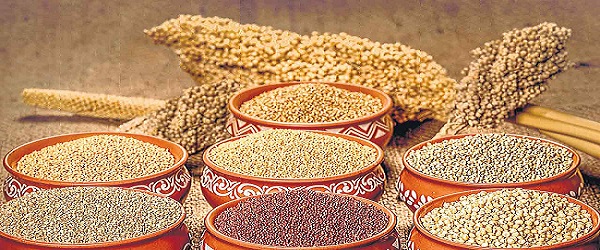

Millets constitute only 5–6 per cent of the national food basket currently but have gained the status of super grains.” Millet is a common term for categorizing small-seeded grasses that are now called cereal grains. Some of them are sorghum (jowar), pearl millet (bajra), finger millet (ragi), little millet (kutki), foxtail millet (kakun), proso millet (cheena), barnyard millet (sawa), and kodo millet (kodon).

The first three are the most popular and prevalent across India. They constitute nearly 90% of total millet production, and around 60% of the millets produced in India are bajra, according to the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA).

Millets have been in vogue since the Indus Valley civilization. They find mention in the Yajurveda too, where foxtail millet is called priyangava, barnyard millet is called aanava, and black finger millet is called shyaamaka. Millets received some attention in 2012, when the then government crafted a policy called the Initiative for Nutritional Security through Intensive Millet Production.

In 2018, millets were declared “nutritional cereals” and added to the national food security mission. Rs. 300 crore was earmarked for its development. It was also in 2018 that India proposed to the UN that it declare 2023 the International Year of Millet. Millet received a shot in the arm when the government earmarked an outlay of Rs 800 crore for millet-based products under its production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, and 33 applicants were selected.

This year’s Union budget announced funding for the Indian Institute of Millets Research in Hyderabad for R&D. The government has also provided a $500,000 grant to the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN to promote millets.

The economic benefits of millets are obvious—they are cheaper to grow. These hardy crops are drought-resistant and require very little water to grow. Some can grow on their own as weeds, even in rocky terrain.

Rice, in comparison, guzzles water, while wheat too needs far more water than a millet crop. Millets also don’t require expensive fertilizers and pesticides. When the climate is changing for the worse, rains are erratic, earth and water are getting poisoned with pesticides, groundwater levels are falling, and farmers’ profits are always threatened by crop failures and rising input costs, aren’t millets the best deal, especially after the acute wheat shortage the world faced due to the Ukraine war? What has stopped us from diversifying into millets? To begin with, millets being cheaper, they hold little attraction for farmers as they offer low margins. Second, the government does not buy them or offer a minimum support price (MSP) for them as it does for wheat and rice, which are part of its food security programme. Bajra, ragi, and jowar are covered by the MSP, but farmers have to struggle to sell these crops at the MSP.

Now the government is considering including certain naturally growing millets in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand in the MSP. Also, millet needs to find a place in the government’s mammoth free food grain programme for farmers to start growing these crops. On top of the government’s demand-side measures is to boost exports of millets and millet-based products.

The $100 million target India is drawing up a roadmap to figure among the top three exporters of millets by 2025, improving upon its fifth rank at present. Canada, Russia, and Ukraine are the top three exporters of millets, followed by the US. Global exports of millets increased to $402.7 million in 2020 from $380 million in 2019. In 2020–21, India exported millets worth $42.8 million, compared to $26.7 million in 2019–20, mainly to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Nepal, Oman, the UK, Japan, Taiwan, and South Africa. India has a nearly 40% share of global millet production, but it exported 1% of its millet production in 2021–22, earning $64.28 million (over $59.75 million in 2020–21), according to APEDA.

While Canada, Russia, Ukraine, and the US are importing millets and exporting value-added products. India just exports millets, according to APEDA. India’s share of value-added products in millets is almost negligible. India has now begun to conduct better research to increase the shelf life of millet products and to manufacture more efficient processing machines.

APEDA is leading the effort to ramp up exports. It has set an export target of $100 million by 2025. “APEDA will push value-added and processed forms of millets globally, targeting various hypermarkets and retail chains. We have identified the top 50 countries, exporters, importers, and supply sources linking production bases,” APEDA Chairman M Angamuthu told ET recently.

Through the diplomatic missions, APEDA wants to reach out to leading department stores, supermarkets, and hypermarkets in those countries to promote millets through food sampling and tasting campaigns. There would be branding and publicity for Indian millet in the targeted markets.

On December 5, APEDA held the first international buyer-seller meet on millets in New Delhi. About 50 mission heads from multiple countries, 35 importers from 18 countries, and 75 Indian embassy representatives participated in the event.

The government is in the process of creating HS codes for smoother exports of millets.

The global millets market is projected to register a CAGR of 4.5 per cent between 2021 and 2026, according to a government statement. Since the government has decided to promote millet in a big way and consumers are becoming more aware of it, businesses are warming up to the opportunity.

Millet march

The G20, under India’s presidency, has been serving millet delicacies to its guests. While the government is pushing for millets, it is important that India’s private sector—in food processing, hospitality, and restaurant spaces—steps forward to get millets back on the Indian menu and plate.

As per the World Economic Forum, higher average global temperatures and extreme weather events associated with climate change will reduce the reliability of food production. The Harvard Business Review has said that food production has to go from 68% to 98% by 2050 to take care of the nearly 10 billion people. This is all the more reason to grow and popularize millet.

Millet consumption will increase only when it becomes a part of monthly, weekly, or daily staples. It is important to make them affordable and accessible and build an affinity around them. This is possible only when chefs, restaurants, and households start churning out innovative delicacies. It is heartening to see millets gradually popping up on the menus of millet-focused restaurants in cities like Chennai, Hyderabad, and Visakhapatnam. Many food start-ups have also come up with various millet-based crunchy options. It is important for millets to permeate the menus of street food, local restaurants, fine dining, and five-star restaurants.

Millets can help the FMCG industry during disruptions in global food grain supply chains, as happened due to the Ukraine war, or adverse climate conditions such as erratic monsoon rains that bring down the wheat and rice output. When raw materials get scarcer and costlier, they crimp the margins of FMCG companies.

Food and beverage producers in India are adopting millets in a big way. You can find millet in a range of products, from biscuits to beer.

From packaged foods to breweries to restaurants, large companiesincluding Nestle, ITC, Britannia, HUL, Tata Consumer, Bira 91, and Slurrp Farm are putting up ambitious plans to introduce millet-based packaged foods, beers, and restaurant menus or boost their existing millet portfolios.

It is delightful to see large agro-based conglomerates like ITC launch their ITC Mission Millet, wherein the enterprise has leveraged the synergy of its food and hospitality businesses. There are learnings from ITC’s Millet Mission, which focuses on the 3 E’s: educate, empower, and encourage. This involves educating consumers on the nutritional benefits of millets, empowering farmers with knowledge on millet crop farming to enhance their livelihoods, and encouraging people to try and build a taste for millet products. The company’s agribusiness is focusing on millet by building integrated millet value chains through farmer producer organisations.

To develop a taste for millets amongst consumers, the company has been introducing millets across its various product categories, such as pasta, snacks, and even candies. ITC Hotels has taken the lead to create and serve recipes with millets, which is a great way to get these onto the plates of those looking for healthy options in their menus. Since October 2022, ITC Hotels have been showcasing millet offerings in their breakfast, lunch, and dinner buffets.

Nestle, which makes Maggi noodles and KitKat chocolate, has already inked a tie-up to integrate millets into its foods. A Nestle R&D Centre India spokesperson told ET recently that a MoU has been signed between millets incubator startup Nutrihub, the ICAR-Institute of Millets Research, and Nestlé’s R&D Centre, a subsidiary of the Swiss foods maker’s parent company Nestle SA.

HUL has signed a MoU with the Indian Institute of Millets Research (IIMR), which has been named a Centre of Excellence by the government, to make millet-based drinks under its Horlicks brand, executives aware of the developments told media.

Taj Mahal Palace in Mumbai sources various kinds of millets for risotto, tehri, and khichdi. Besides big companies, new breeds of entrepreneurs are selling millet products. Pune-based Sharmila Oswal, who calls herself a milletpreneur, is a co-founder of Basillia Organics. In the last two years, it has exported millets to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the US, the Netherlands, and Australia. Her products include millet noodles, millet cookies, millet namkeen, and millet pasta. She nudges parents to pack millet lunch boxes for their children. Consumers are willing to pay a little more because millets are nutritious. Once production grows, prices should come down.

The Indian Institute of Millet Research has identified 200 new entrepreneurs of millets. The startups are creating value-added products, and many of them have started exporting in small quantities. We are promoting them through international fairs.

Editors’ view

One of the crucial reasons that millets are important is because they can help the world face the challengeof food security. Resilient seeds like millet provide an affordable and nutrient-rich option. This is why promoting their cultivation and consumption can help empower smallholder farmers, achieve sustainable development, and transform the agrifood system.

So why is modest cereal essential to India? One of the fundamental reason’s millets play such an important role in India is that it is a hardy grain that can grow in an environment with less water and other agricultural inputs. Grown in the Kharif season, millet production has the ability to generate livelihoods, increase farmers’ income, and ensure food and nutritional security.

The only glitch is that without a growth in consumption of millets, there won’t be enough demand to motivate farmers to switch to cultivating the cereal. Therefore, increasing consumption domestically to help farmers within India and drawing attention to this often-ignored cereal globally could serve as a means to support agrifood systems and feed the burgeoning global population.

Also, consuming millets is extremely healthy. Not only is it a nutrient-dense cereal, but this fibre-rich grain has also been known to help control blood pressure and blood sugar levels. Therefore, the production of millets is central to encouraging its consumption and is a step towards meeting future demand.

On the governmental front, while suggesting and declaring the IYM as a positive step towards increased demand and consumption of millets, there is a need for policy-level interventions to ensure that farmers get remunerative prices for millets. It will also help them get a higher return on investment (ROI) than crops such as paddy. Presently, even though the MSP of millets has grown by 80–120 percent (between 2013–14 and 2021–22), the combined production of ragi, bajra, jowar, and millets has dropped by 7 percent.

As per the Department of Commerce, the export of millets is expected to increase exponentially in the near future. Indian exporters are now discovering new markets globally, and as per 2020 data, India is the fifth-largest exporter of millets globally.

Further, the global millets market is now projected to register a CAGR of 4.5 per cent during the 2021–2026 period. Finally, millets are believed to be one of the earliest cereals to be cultivated in India. But a few years after Indian independence, India was faced with a severe food shortage and had to quickly pivot to find a solution. The Green Revolution promoted cultivating wheat and rice, which helped forestall such a predicament.

So, to build the production of millets, demand and consumption are key. But more importantly, increasing the adoption of millets as an integral part of one’s daily diet as opposed to rice or wheat will be fundamental.